Chinese Companies with Winning Stocks do More than the Minimum

By Oliver Rui

After observing that the stock of mainland-listed companies usually beats the market when foreign investors hold more than five percent of the shares, a Goldman Sachs analyst suggested recently that investors should look for companies with relatively high foreign ownership when buying Chinese shares.

The findings of some of my own academic research offer some explanations for this trend, and suggest three things to know about Chinese companies, and those from other emerging markets, before investing: foreign ownership, institutional investors and political connections. Since many factors can influence stock performance, I can’t say with certainty that these things will guarantee good stock performance. But I have seen evidence of how they have had a positive effect on the governance and transparency practices at Chinese listed companies, and that often signals better potential for a good performance.

So how do foreign ownership, institutional investors and political connections nudge emerging market companies towards following better governance practices? Let’s start with foreign ownership. China’s B-share market provides us with a good laboratory for exploring this because of changes made to market regulations. The B-share market began in 1991 as a way of allowing domestic enterprises to attract international capital. B-shares are legally identical to A-shares; their main difference is that all transactions, dividend payments, trades, and quotes are conducted in a foreign currency: US dollars for Shanghai B-shares and Hong Kong dollars for Shenzhen B-shares. Initially only foreign investors could buy B-shares, and regulators required firms that issue both A- and B-shares to publish two sets of financial statements. The one prepared for A-share investors had to be in accordance with Chinese Accounting Standards, while the B-share investor report was done in accordance with the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). Companies could choose whether or not to use one of the Big Four accounting firms to conduct their B-share audit. Because the Big Four require companies meet high-level global compliance standards, it follows that a Chinese company who chooses to hire one of them would have better governance and transparency standards, which is a concern for most foreign investors.

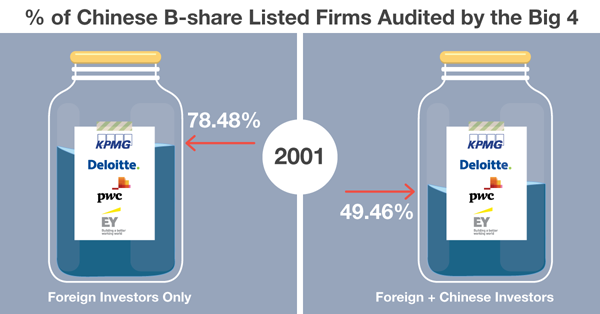

Regulators changed the rules in 2001 to allow Chinese to invest in the B-share market. So my co-authors and I did a study to see if there was any change in the number of Chinese companies using a Big Four auditor when they no longer needed to rely on foreign investors to buy their B-shares. After analyzing data for 1,277 B-share firms from 1992 to 2006 (in 2007 regulations changed and made B-share audits voluntary) we found there had been a significant change. Prior to 2001 when B-shares were only available to foreign investors, 78.48% of firms used a Big Four auditor; after the rule change, between 2001 through 2006 only 49.46% did – a decrease of almost 30%.

Another study I did explores the correlation between institutional investors (both foreign and domestic) and political influence and the incidences of corporate fraud among Chinese companies. The results showed a similar trend.

For this study my co-authors and I looked at the companies involved in 966 regulatory enforcement announcements made by the CSRC (China Securities Regulatory Commission), the Shanghai Stock Exchange and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange between 2003 and 2011. The types of violations investigated included illegal share buybacks, inflated profits, fabrication of assets, violations in capital contributions, shareholder embezzlement, price manipulation, and speculation. We began in 2003 because this is when listed firms began disclosing the percentages of their shares held by institutional investors such as mutual funds. We defined a firm as politically connected if it’s CEO and/or Chairman is currently serving or formerly served in the government or military.

We found that both politically connected managers and institutional investors played a role in decreasing the incidence of enforcement action against fraud. However, politically connected managers and institutional investors achieve this in different ways. Politically connected managers tend to prevent firms from being exposed to enforcement action, while institutional investors are more likely to prevent firms from committing fraud.

As these studies show, in emerging markets where governance and transparency standards are less mature, informal governance mechanisms like foreign and institutional ownership stakes and political connections can help investors to better assess a company’s potential performance. It's a good sign when companies elect to follow better governance practices than required. Think of companies like athletes – the ones who stick to a good training regimen are more likely to perform better in competition. Those who eat junk food and rarely exercise are a lot less likely to be winners.

CEIBS Professor of Finance & Accounting Oliver Rui is Director of the CEIBS Center for Wealth Management, Co-Director of the CEIBS Center for Family Heritage, and Zhongkun Group Chair Professor of Finance.

This article was first published by Caixin Global.